Lutherans, Loyalty, and Language The Experience of Lutherans in Seward County Nebraska during World War I

The United States’ declaration of war against Germany in April 1917, significantly impacted people on the home front, those who did not participate in the European battlefield. German Lutherans in Seward County, Nebraska, supported the war effort in many ways and generally were described in favorable terms by the local press. However, as the war progressed, they had to confront accusations of disloyalty and pressures to discontinue the use of the German language in their worship of God. This article will overview the local ethnic character of Seward County at the time of World War I, including its Lutheran population; confirm the Lutheran support for the war effort; and describe the public reasons for loyalty issues prompted by official and unofficial actions toward the Lutheran church.

Seward County lies directly to the west of Lancaster County, Nebraska, the location of the state’s capital, Lincoln. It was and is a rich agricultural area. The population of Seward County grew rapidly after the state’s admission to the Union in 1867. The 1870 Census reported 2953 residents; the 1910 Census reported 15,938. The county was ethnically diverse with residents from Anglo-Saxon, German, Czech, and Danish backgrounds. A sample of German-born residents in 1900 showed they comprised almost 10% of the county’s population.1 That diversity was reflected in the religious makeup of the county with Methodist Episcopal, United Brethren, Congregational, Presbyterian, Reformed, Roman Catholic, Mennonite and Lutheran congregations, among others.

Lutheranism was well established in the county by the time of World War I. There were fourteen congregations in various parts of the county, eleven of them German-speaking—eight of these in the Missouri Synod, one Iowa Synod, and one Wisconsin Synod, one unaffiliated—and three were Danish.

St. John’s Lutheran Church in Seward was the largest of these. The Missouri Synod congregations had schools which played an important role in preserving the cultural heritage of the members.2 The City of Seward was home to the Evangelical Lutheran Teachers Seminary (or “Lutheran college” as the press referred to it), today’s Concordia University, founded in 1894.

Impressions gathered from county newspapers indicated that the Lutheran congregations, even though their primary worship language was German, were an accepted part of their communities. For example, the Utica Sun (US) and the Seward Independent-Democrat (SID) regularly printed notices of the Sunday worship services, including when they offered English services. The US in June 1912 described the successful mission service of the German Lutheran Church (today’s St. Paul’s), which was well attended and which collected over $100 for mission work.3

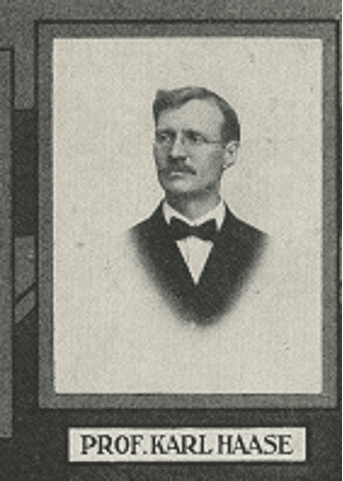

The SID publicized major events and activities at St. John’s Church. It published a lengthy article on the dedication of the congregation’s third church in August of 1910, including a detailed description of the altar, pulpit, pews, and stained glass windows. Over 3,000 people attended the three services (two in German, one in English). A special train brought people from Lincoln, Malcolm, and Germantown. Others came on regular trains from Utica, Hampton, Waco and other towns. It included photos of the first, second, and new buildings. It especially commended Pastor C. H. Becker and Professor Karl Haase, director of the congregation’s music program and professor of music at the Lutheran college.4

The newspaper reported on the music program of the congregation. In June 1912 the congregation and college arranged a special music service with the German Lutheran congregation in Lincoln. A special train carried musicians from Seward, along with congregational members to Lincoln, stopping in Germantown (now Garland) and Malcolm for people who wanted to attend this special event. Some 175 singers and three organists participated in the service. The following week the program was repeated, this time people from Lincoln coming to Seward.5 In May, 1916, the choir of the congregation celebrated its tenth anniversary with a special song service, in which the college choirs also participated. The newspaper printed the entire program for these two concerts.6

More evidence of acceptance of Lutherans in the community, this one after the war declaration, was the publicity in the local press given to the Seward County Lutheran churches’ celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Reformation in October, 1917. A large tent, able to seat 4000 people, was erected in the fair grounds of Seward. Three services were held that day. The morning service was in German. The afternoon service was primarily in English, but with English and German sermons. The evening service at St. John’s Church was in English. Choirs from Lutheran schools and congregations in the county as well as from Lincoln and Columbus and the college, numbering about 500 children and 250 mixed voices as well the college orchestra, provided music for the occasion. An estimated 4000 individuals attended the morning service, 5000 in the afternoon, and over 1000 in the evening services. An element of patriotism was present through American flags and display pictures of George Washington, Woodrow Wilson, and Martin Luther.7

The Seward County Home Front in World War I, 1917-1918

Generating Support for the War

When the war came many patriotic activities and organizations endeavored to heighten and maintain the county’s support for the war. In early May of 1917 the City of Seward organized a large patriotic meeting. Memorial Day events in 1917 and 1918 featured parades, including the Lutheran college band and students from the public and Lutheran schools. Patriotic meetings occurred in Beaver Crossing, Germantown (now Garland) and Seward during the summer of 1917. The Chautauqua programs, presented in each community in those years, focused on the war effort.8

The most drastic impact of the war was the enlistment and drafting of young men into the armed forces, many of whom fought against Germany in France. County communities honored these men with special sendoff events. In September of 1917 the city of Seward organized a parade to recognize draftees. Some 3,000 people attended a meal in the city park. A few days later Staplehurst held a patriotic festival to support their own draftees with a supper and speeches. The following week the second contingent of 53 men departed for Camp Funston in Kansas. A group of 300 residents from Beaver Crossing came in 90 cars with the inductees. The Commercial Club in Seward had a meal for the men, after which the band from the Lutheran college and other local musicians escorted the draftees to the local train depot.9

Churches joined the effort in various ways. In early July there was a large patriotic worship service in which the Rev. Bert Story, of the Methodist Episcopal church, and the Rev. W. E. Ludwick, of the Congregational church, spoke. Both of those pastors were extremely active in patriotic events. In April of 1918 the SID called for a patriotic “Go-to-Church Sunday,” asking every pastor to make it a “patriotic holy day” exhorting that “The entire day should be given over to patriotic prayers, patriotic sermons, and Liberty talks.” Pastor C. H. Becker of St. John’s Lutheran Church chose an alternate course. Following the regular morning service on May 26, 1918, he gave a special address to the congregation on “Love of Our Country.”10

Becker’s message was both a thoughtful and passionate appeal to his parishioners to support loyally the nation’s war effort. He called the listeners’ attention to the names of the seventeen members of the congregation who were serving in the armed forces. He told the members that when they worshipped, they could give thanks for the national flag which stands for liberty of conscience, press, speech, and religion. He urged them to unite with all citizens in defense of liberty for which the flag stands. He stated, “We . . . members of St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church of Seward, Nebraska, love our country above all countries . . .” because of democracy and free institutions. In his mind, religious liberty distinguished the United States above every country in the world, and he implored God to preserve the nation from any state church and all forms of religious oppression. He concluded his message in these words: “Most willingly do we render unto our beloved country all due service and obedience to Him from whom all blessings flow.”11

Seward residents were encouraged to support two non-governmental organizations which assisted in the war effort: the Red Cross and the YMCA. The county supported the Red Cross, along with the Red Cross Hospital Supply program, through several fund drives during the war years. In June 1917, the city Red Cross committee announced a fund drive of $16,000 and a campaign to secure more Red Cross memberships. Several local merchants, banks, and physicians financed large ads in the SID encouraging support for this drive.12 By late September over $2500 had been subscribed in the county. The SID singled out St. John’s Lutheran Church for its large subscription of $1648 to the county quota, stating that the entire city of Seward did not match that.13

In November of 1917 the Red Cross county chapter elected new officers and members of the Board of Directors, among them F. W. C. Jesse, president the Lutheran college, and Anna Haase, wife of the college’s music professor. Jesse also served on the Executive Board of the county chapter. In December a “Red Cross Appeal” sought additional funding and a drive for new members. At that time about 30% of county residents were members, but the organization hoped it would go higher. The Seward City branch organized for the drive, appointing leaders for various districts of the community. Among them was J. T. Link of the college faculty. According to the SID, the Christmas drive was a major success, with over $7000 raised and substantial increases in membership. In April of 1918, the members of Zion Lutheran Church in Marysville, near Staplehurst, contributed over $500 to the campaign. The Marysville district, heavily Lutheran, claimed 100% membership in the Red Cross.14

The YMCA provided many services—spiritual, recreational, and educational—for service men in military camps. In November 1917 the Seward County YMCA organization sent two representatives from the county, R. S. Norval, a prominent lawyer, and Pastor C. H. Becker to examine first-hand the work of the YMCA in Camp Funston, Kansas, specifically to learn whether each religious denomination had a designated time for worship services at the YMCA center on Sunday mornings. Seward had received conflicting reports. They learned that there were no denominational services offered by the center, but that representatives of denominations were allowed to meet with servicemen who also were allowed to attend services in churches of their choice in nearby towns. The YMCA did not compel soldiers to attend any specific service. Their religious freedom was protected. The two men evaluated positively the work of the YMCA and were fully satisfied.15

The two previous programs were non-governmental, but cooperated closely with the national government in the war effort. The next three programs were governmental programs, designed to stimulate patriotism and to raise funds to cover the enormous expenses caused by the war.

Four-Minute Men was a national government effort to promote loyalty and disseminate war-related information throughout the country. Men in the communities, often prominent local leaders and pastors, would give short messages on various war-related themes at local movie theaters between changes of film reels and in other public locations. Themes included “Men and Morale,” the Red Cross, Liberty Loans, and “The Danger to Democracy.” According to the SID, the Seward County “Four-Minute Men” by mid-October of 1918 had addressed some 80,500 people and won honors as the most efficient of these branches in the state. Pastors of many churches were accredited as Four-Minute Men. Lutheran pastors were among them: C. H. Becker, F. W. C. Jesse, E. George Weller, and Theodore Evers of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Utica.16

The War Savings Stamps (WSS) program began in late 1917. It allowed individuals to purchase a War Savings Certificate, originally for $4.12, which would be worth $5.00 at maturity in five years. People also could purchase 25-cent Thrift Stamps which they affixed to a Thrift card until they accumulated 16 stamps. Then they could purchase a War Savings Certificate stamp. A related option was to purchase “Baby Bonds” in denominations up to $1,000.00. Individuals who purchased these became members of the “Limit Club.” The SID regularly published the names of those who had invested the $1,000 in the WSS program. Some members of St. John’s joined that group.17

The first War Savings Stamps drive took place on January 18, 1918. The Executive Committee of the program asked County School Superintendent W. H. Brokaw to dismiss classes that afternoon to hold fund-raising meetings in the schoolhouses. The Seward County quota was $320,000, half to be raised at the initial gathering. The event was a great success. According to the SID over 5000 men attended, and men of German heritage were in the forefront. They exceeded the quota and exhausted the supply of certificates. The suspension of schools on Friday afternoons for subsequent drives was soon adopted by the entire state of Nebraska. The SID published lists of those who subscribed as well as those who attended but did not subscribe and people not attending. Students in a number of school districts participated in the Thrift Stamp program. Pastor C. H. Becker and Professors George Weller and F. W. C. Jesse served on the City of Seward committee, along with pastors Bert Story (Methodist) and A. Woth (Evangelical Friedens Church). The SID commented on March 7 that lending money for the war effort was a sign of patriotism. How individuals responded determined their loyalty.18

The major borrowing program for the war was Liberty Loans. Four drives were held during the war (1917 – 18) with a fifth after it. Seward County responded positively to all four wartime bond issues. Merchants agreed to close early on April 6 when the Liberty Loan program began in Seward. The Seward community organized a large parade which was more than six blocks long, “in close order,” according to the SID for that date. Many organizations participated in this celebration, including the college band. That paper encouraged pastors of churches and teachers to preach and teach in support of the third Liberty Loan drive. In its announcement regarding services on Sunday May 12, 1918, St. John’s reported that its members to date had contributed $63,772.64 to war activities—Liberty Bonds, War Savings Stamps, Red Cross, YMCA, and Armenian and Syrian relief. Approximately two weeks later the US Treasury Department sent a letter to Pastor Becker of St. John’s commending the congregation for its generous support.19

The County Defense Council of Seward and Vigilante Violence

Insuring Loyalty and War Support during World War I, 1917 - 18

On April 25, 1917, less than three weeks after Congress declared war on Germany, the Nebraska legislature established the State Council of Defense. Its mission was extensive: to create a high level of effectiveness in pursuing the war effort in areas such as agricultural production, food conservation, and Liberty Loan drives. However, it increasingly focused on financial support of the war and on matters of loyalty, especially by German-Americans. In May 1917 Governor Keith Neville directed each county to organize county defense councils. Seward County already had done so.20 The Seward County Defense Council (CDC) consisted of one member from each precinct, plus one representative from each of the City of Seward’s two wards. J. J. Thomas, a well-known lawyer and judge, chaired the CDC. Some precincts created their own councils of defense.21

In addition to the official work of the CDC, there were occasional outbreaks of “vigilante” violence against individuals suspected of disloyalty.

An early example of that grew out of rumors about Paul Becker, the son of Pastor C. H. Becker of St. John’s Lutheran Church and an employee of the Curry Brothers clothing store. Becker’s name was drawn early in the draft lottery. On July 30, 1917, he married Emma Reckeway of Sterling, Nebraska. He was accused of getting married to escape the draft. (Having a dependent or dependents was a legal cause for exemption.) In addition, stories circulated that the Curry brothers planned to file an exemption claim on behalf of Becker. On August 14 the front of the Curry store was painted in yellow with words such as “slacker” and “traitor.” According to the SID, newspapers in other parts of the U.S. printed this story.22

Paul Becker wrote a letter to the Local Board of Exemption on August 18 indicating that he had withdrawn his claim for exemption and that intended to volunteer and go to Fort Snelling with other men from Seward. He asserted that his father and the Curry brothers had been slandered by accusations that they had induced him to marry to claim a draft exemption. The county draft exemption board confirmed that the Curry brothers had never sought an exemption for Becker. Becker also wrote a separate public letter explaining the situation.23 In October the CDC reported on the event, concluding that the rumors were false. It hoped that no further incidents of this type would occur. These phony accusations were not signs of patriotism or loyalty but were grave injustices against the loyal Curry brothers.24 On September 22, 1917, Paul Becker joined a group of draftees and departed for Camp Funston, Kansas.25

In early February 1918 a group of “super patriots” broke into the high school in Seward and stole all the German-language books used for an elective course. A week before the incident the Seward chapter of Daughters of the Revolution had sent a petition to the Board of Education requesting that German courses be discontinued. School Superintendent Moritz said that students could study German only if they petitioned to do so, and twenty-two had done that. He added that the school kept the course for students to meet certain entrance requirements for Nebraska University.26

Language, Lutherans, and Loyalty

As the war continued, the State Council of Defense and the County Defense Council gave increasing attention to allegations of disloyalty especially among those of German Lutheran descent and the use of foreign languages in public places. In 1919 nearly half the population of Nebraska consisted of white persons of “foreign stock,” that is, foreign-born or having one or both parents who were foreign-born. Of that group, forty-eight percent were of German, Austrian, or Hungarian roots—the enemy nations in the war. Most of them spoke English, typically along with German.27 Many Nebraskans questioned the loyalty of this group toward the nation and its war effort. That suspicion had major consequences.

Perhaps anticipating anti-German sentiments the Lutheran college, often called the “German college” locally, erected a 100-foot flagpole on its campus as a symbol of loyalty. According to the SID on May 29, 1917, “occured [sic] the most impressive flag raising ceremony that has so far occured [sic] in this county.” The college band played “martial” music, and Mayor Harry A. Graff, School Superintendent Brokaw, and college president F. W. C. Jesse addressed the crowd. Those gathered sang the Star-Spangled Banner while the flag was raised.28

Nevertheless, in August the SID questioned the loyalty of three of the college’s professors, Paul Reuter, J. T. Link, and H. B. Fehner. They had canceled their subscriptions to the SID, accusing the newspaper of being excessively patriotic. The following week Link responded, asserting that he had no objection to the paper’s patriotism, but he did fault its reprinting the scurrilous “The Kaiser’s Prayer,” a satirical doggerel intended to mock Wilhelm II. He found it offensive, saying that it violated the divine principle, “Thou shalt not use the name of the Lord thy God in vain.” The editor accepted Link’s statement and expressed regret at misunderstanding Link’s cancelation of his subscription.29

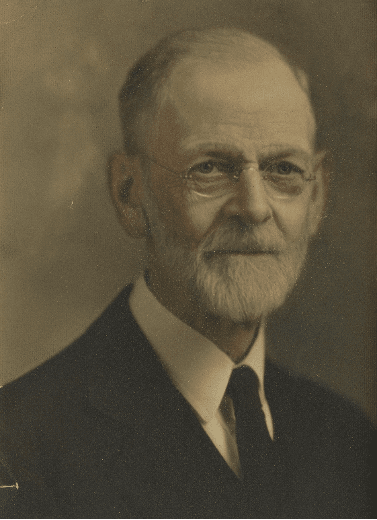

In July 1917 the State Council of Defense charged nearly all the leadership of the Lutheran church with refusing to support the government and discouraging “the American cause.” It called on members of the Lutheran church to counteract the tendencies of their leaders.30 The SID invited President F. W. C. Jesse of the Lutheran college to respond, and he did so willingly. He cited confessional documents of the Lutheran Church—the Augsburg Confession, the Large Catechism, and the Small Catechism—to show that Lutherans were to be subject to and serve government. Jesse stated that “the Lutheran church stamps disloyalty as a disgrace before men and rebellion against God.” He had told his students even before the war began that they must stand behind the flag.31

Later in the war, on June 10, 1918, the college musicians gave a Patriotic Open Air Concert at the end of the school year, with much of the music related to the war effort. The concluding piece was Sousa’s “Stars and Stripes Forever.”32

Toward the end of 1917 pressure grew against parochial schools which taught in German or taught German. The State Council of Defense requested a meeting with a Missouri Synod delegation. George Weller and J. T. Link from the college represented the synod but were unable to persuade the council that the teaching of German did not mean that students in Lutheran schools were indoctrinated into German “ideals.” On December 12 the council ordered the banning the teaching and use of all foreign languages in Nebraska schools. Weller and Link had little option but to accept the council’s order even though they doubted its legality.33 At a meeting in Seward later that month, pastors and delegates from Lutheran schools in Nebraska unanimously voted to cease all use of German in their schools. The Lutheran school at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Utica closed and sent their students to the public school.34

The movement against the use of German persisted. Late in May 1918 the CDC considered a proposal to ban the use of all foreign languages in public places. George Weller and F. W. C. Jesse requested the privilege to address the meeting of the CDC. Weller stated that he basically agreed with the resolution; he favored limited use of German in public places, but urged that it be permitted in churches. The proposed resolution would have banned German in churches entirely. Weller express concern about elderly pastors and some members who had limited English skills. He noted that German already was not used in schools. He favored the resolution as it pertained to businesses, but not for churches. Judge Thomas, chair of the CDC, responded that he wanted a common language for all people. The ongoing use of foreign languages had led to the failure of “Americanization.” Mayor Harry A. Graff, a member of the CDC, responded that the U.S. had invited people to come to our country, and that it would be wrong to abolish in a single stroke what we had fostered. He favored the exception of religious services in the resolution.

Jesse, who said that he had preached more in English than in German, contended that the resolution was on dangerous ground. No church was disloyal, and the Lutheran church had no reason to sympathize with Germany. He pleaded on behalf of older people and cautioned against harsh measures. He stated that when people come to church, they approach God. He concluded, “Let us keep hands off.”

The CDC passed a resolution by a vote of 7-5 urging restraint from using “all foreign tongues” whenever possible, especially in public places. This did not apply to religious services, but it urged the use of English wherever possible. The resolution stated that the use of foreign languages had led to the failure to inculcate American ideals and the love of free institutions.35 A couple of weeks later the SID included a brief note saying that the State Council had issued a proclamation asking people to avoid using all foreign languages in public places. The editor concluded that this position coincided with the action of the local CDC. A week later the CDC resolved to print notices about its position and send them throughout the county.36

The matter was not over, however. In July the State Council of Defense “tightened the noose” further, declaring that the “main” service in every church had to be in English. It did allow, however, for “private religious instruction” at a different time for those without knowledge of English. The Seward CDC endorsed the position of the State Council and notified all county churches.37

St. John’s Lutheran Church in Seward called a special congregational meeting on July 21 to address the new rule. Pastor C. H. Becker now faced a situation quite different from that in May when he praised the United States for its protection of religious liberty. Becker had thoroughly prepared a lengthy and forceful statement for the assembly. He clearly was anguished, torn between his loyalty to the United States and the treatment of his people at this time. He stated, “It [the Lutheran church] is what you would expect of her. Her loyalty is of the nature of a divine force. Apology, Art. 16: ‘The Gospel requires us to be obedient to the government.’” He reviewed the history of Lutheranism in the colonial and revolutionary eras in terms of how it supported freedom of religious practice. The Missouri Synod had pledged its loyalty. He noted that the Missouri Synod members had invested more than $20,000,000 in the Third Liberty Loan drive. He cited the Constitution of the State of Nebraska that it was the “. . . duty of the legislature to protect every religious denomination in the peaceable enjoyment of its own mode of worship . . . .”

Becker deplored the treatment of his people. “They [the State Council of Defense] are doing an ill service who are hampering the Lutheran church in her works.” “We protest this movement [of restricting the use of foreign languages] as involving an abridgement of our glorious American liberties.” He continued:

“(W)e are being met with sneers and calumnies. . . It is a bitter experience . . . to be branded as disloyal and treated as disloyal by various special rules and regulations while we are giving the full proof of loyalty . . . .”

Now the Lutheran church had to be “doubly” loyal. The action of the CDC abridged constitutional liberties and committed an injustice. He hoped that his people would not be forced to give up German completely. Nevertheless, he stated that “. . . where the constituted authorities ask it, or inflamed public sentiment comes into consideration, our officers are counseling compliance, and our people are bravely making the sacrifice.” He urged forbearance in the current situation and acceptance of the CDC’s position. After lengthy discussion, the voters agreed to comply with the request of the CDC. St. John’s then began to conduct the main Sunday service at 11:00 a.m., with a German service at 10:00.38

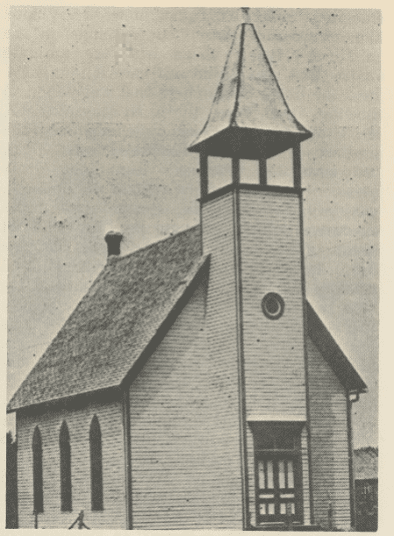

St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in Utica also felt the effects of the CDC decision. In July, 1918, it announced that Sunday mornings would alternate between German and English, and that on the last Sunday evening of each month they would have an English service. The US reported on July 18 that the CDC was distributing signs to every business in the town reading, “This is America, Speak the American Language.” The paper’s editor commented that the use of German was irritating to patriotic citizens and aroused suspicions. For this reason the CDC was trying to eliminate the use of all foreign languages. He concluded, “Americans should speak the American language.” On August 8 the Sun included the statement of the state council regarding the use of English only in the main service on Sunday mornings. St. Paul’s church notice announced an 11:00 a.m. service. No longer did it have English and German worship on alternating Sundays.39

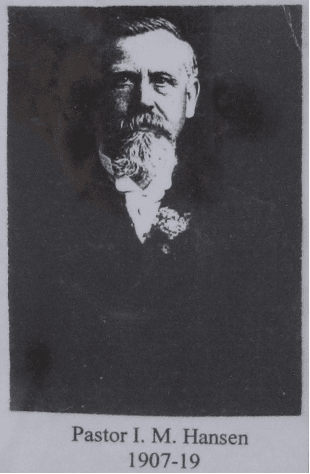

Not only German Lutherans were affected by the CDC’s position. In early August, Ivan Marius Hansen, the pastor of the Danish Our Savior’s Lutheran congregation in Staplehurst, appeared at a CDC meeting asking that the language rule be held in abeyance and not be enforced on him and his congregation. He said that while he had some knowledge of English, he could not conduct a service in that language. Members of the council seemed sympathetic to his plea, but refused to make an exception. The result was that Pastor Hansen soon resigned his pastorate at Staplehurst, as well as from his church in Bennett. He said that he was 60 years old and would now have no home nor work, but that he had no choice.40

An unexpected outbreak of tension regarding the language issue occurred at a meeting called by the War Stamp Savings committee in the Staplehurst area on August 1, 1918. Henry C. Richmond of the State Council of Defense was invited to be the principal speaker. He made positive remarks about Staplehurst and Seward County. He addressed the problem of the Lutheran church with the council, but exonerated churches and several clergy in the county.

Following Richmond’s address, Pastor W. F. Rittamel of Zion Lutheran Church in Marysville unexpectedly spoke at considerable length. He complained that the Lutheran church had been maligned. He insisted that the Kaiser was not Lutheran, nor was the state church of Germany. Lutherans had come to the US for religious freedom and had no use for the Kaiser. He claimed that Lutheran schools were more patriotic than public schools. Rittamel argued that Lutherans preferred the German Bible because it was written in the language of the people. In contrast, the English translation was difficult to understand. He closed by expressing his pleasure at meeting Richmond. Richmond responded, “Well, I am mighty sorry you made that speech.” Following the meeting some of the attendees spoke in small groups, the general sentiment being that Pastor Rittamel’s speech was regrettable.41

An interesting note on which to conclude this discussion was that in mid-August, 1918, President F. W. C. Jesse of the Lutheran college was appointed by Nebraska Governor Neville to a nine-man Americanization committee whose purpose was to assist foreigners to understand U.S. traditions and values.42

Soon the war would end and some of the tensions over CDC restrictions on religious worship would ease. However, the Nebraska legislature passed the Siman act in 1919, prohibiting teaching in any language besides English through the eighth grade. That law was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in the important decision in Meyer v. Nebraska (1923). The issue of use of foreign languages in a diverse society such as the United States predated the U.S. entry into World War I and would extend beyond it.

The War's End

On November 11, 1918, news arrived at 3:20 a.m. by telegraph at the Seward depot that the war indeed had ended. Quickly the fire bell began ringing, continuing until 6:30 a.m. Men were firing guns in the air and whistles were blowing. The city band was playing in the streets. The SID specifically praised the students at the Lutheran college for their “noise-making” celebration. When news reached the campus, they started ringing the campus bell and blowing their horns to alert others, who quickly were out to celebrate the exciting news.

L. E. Ost, the chair of the Victory committee, gathered his members to plan a celebration. By 8:30 the city was decorated with flags and bunting; anvils were fired. At 7:30 that evening a large peace celebration began. The city and college bands both participated, and there were large crowds of people and several blocks of cars. The parade stopped at the northwest corner of the square to have a shooting-in-effigy of the Kaiser hanging from a phone cable. At the fairgrounds, people built a bonfire twenty-five feet high, with an outhouse—called the kaiser’s cabinet!—at the top. Twelve barrels of tar were used to speed the fire. More effigies of the Kaiser and his six sons were hung between trees and burned. The choir from the college performed. By 9:00 the event was quieting down.43

The war was over. Seward County had endured tensions over foreign languages, alleged Lutheran disloyalty, and vigilantism. Overall, Lutherans in the county strongly supported the war effort through material, financial and moral support, and its willingness to make concessions to civil liberty and personal convenience in the face of wartime exigencies.

References

1 Frederick C. Luebke, Immigrants and Politics: The Germans of Nebraska, 1880 - 1900 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969), 58, 193.

2 Luebke, Immigrants and Politics, 47.

3 Utica Sun(later cited as US) June 6, 1912, 4.

4 Seward County Independent (hereafter cited as SID), August 18, 1910, 3. Luebke, Immigrants and Politics, 44-45, states that this newspaper tended to get support from political and social outgroups, which would include German-Americans. The SID is the most important source for this study. It had the largest circulation of county newspapers and generally provided more complete coverage. The Blue Valley Blade (BVB) published a similar article on the church dedication, August 17, 1910, 1.

5 SID, June 6, 1912, 6 and June 13, 1912, 4.

6 SID, May 15, 1916, 1.

7 SID, October 4, 1917, 1 and 5; October 11, 4; Blue Valley Blade, October 3, 1917, 1 and 2.

8 SID, May 10, 1917, 1; May 31, 1917, 1.

9 SID, September, 13, 1917, 1; September 20, 1917, 8; September 27, 1917, 1; November 22, 1917. 1; May 30, 1918, 1.

10 SID, May 28, 1917, 1; July 12, 1917, 1; April, 4, 1918, 5.

11 SID, May 30, 1918, 1.

12 SID, June 21, 1917, 1; June 28, 1917, 5.

13 SID, September 27, 1917, 4; October 4, 1917, 1.

14 SID, November 8, 1917, 4; December 27, 1917, 1; March 7, 1918, 1; April 18, 1918, 7.

15 SID, November 29, 1917, 7.

16 Examples are SID, November 8, 1917, 4; November 15, 1917, 1; November 22, 1917, 1; October 3, 1918, 3; US, January 17, 1918, 1.

17 SID, March, 14, 1918, 2; March 21, 1918, 1; March 28, 1918, 1 and 6; May 2, 1918, 1.

18 SID, January 17, 1918, 2; January 24, 1918, 1; January 31, 1918, 1; March 7, 1918, 2.

19 SID, June 7, 1917, 2; June 14, 1917, 1; November 1, 1917, 2 April 4, 1918, 2; April 11, 1918, 1; may 9, 1918, 4; May 23, 1918, 2.

20 SID, May 10, 1917, 5.

21 SID, May 17, 1917, 1. Frederick Luebke explains that although German-Americans had been rather well received in US society, the war unleashed a powerful spirit of anti-German sentiment and action soon after war was declared. Frederick Luebke, Bonds of Loyalty: German-Americans and World War I (Dekalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1974), xiii, 234-253.

22 SID, August 23, 1917, 1.

23 SID, August 23, 1917, 1.

24 SID, October 11, 1917, p. 1.

25 SID, September 20, 1917, 1; BVB, August 22, 1917, 2

26 SID, February 7, 1918, 1; BVB, February 6, 1918, 2.

27 Jack W. Rodgers, “The Foreign Language Issue in Nebraska, 1918-1923,” Nebraska History 39 (1958): 5-6. See also Niel M. Johnson, “The Missouri Synod Lutherans and the War Against the German Language, 1917-1923,” Nebraska History 56 (1975): 136-144; Robert N. Manley, “Language, Loyalty, and Liberty: The Nebraska State Council of Defense and the Lutheran Churches,” Concordia Historical Institute Quarterly 37 (1964): 1-18; and Frederick Nohl, “The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod Reacts to United States Anti-Germanism During World War I,” Concordia Historical Institute Quarterly 35 (1962): 49-66.

28 SID, May 31, 1917, 8.

29 SID, April 26, 1917, 6; August 9, 1917, 4; SID, August 16, 1917, 8.

30 SID, July 19, 1917, 6; Manley, “Language, Loyalty, “ 4.

31 SID, July 26, 1917, 1 and 8.

32 SID, June 6, 1918, p. 10.

33 Manley, “Language, Loyalty,” 10-12.

34 US, January 3, 1918, 1; January 17, 1918, 1.

35 “County Defense Council Taboos Use of German,” SID, May 23, 1918.

36 SID, June 13, 1918, 2; June 20, 1918, 1.

37 “Drastic Rule Against All Foreign Languages,” SID, July 11, 1918.

38 SID, August 1, 1918, 7; Seward Journal, July 26, 1918, 1; “Eine Extra-Versammlung abgehalten am 21. Juli 1918” (Minutes of a special congregational meeting at St. John’s Lutheran Church, transcription and translation by Joseph Herl.)

39 US July 11, 1918, 4; July 18, 1918, 1; August 8, 1918, 1 and 4

40 SID, August 22, 1918, 3.

41 SID, August 8, 1918, 1; Manley, “Language, Loyalty,” 7. Manley misdated the meeting to August 1917.

42 SID, August 15, 1918, 3.

43 SID, November 14, 1918, 1

Related Stories